Sonia Farmer conducting self-directed research about the Williamson Photosphere

One hundred years ago, a man named Ernest Williamson led the first of six expeditions with two natural history museums that would extract 70 tons of coral, as well as several hundred fish and related sea life, from the waters of The Bahamas.

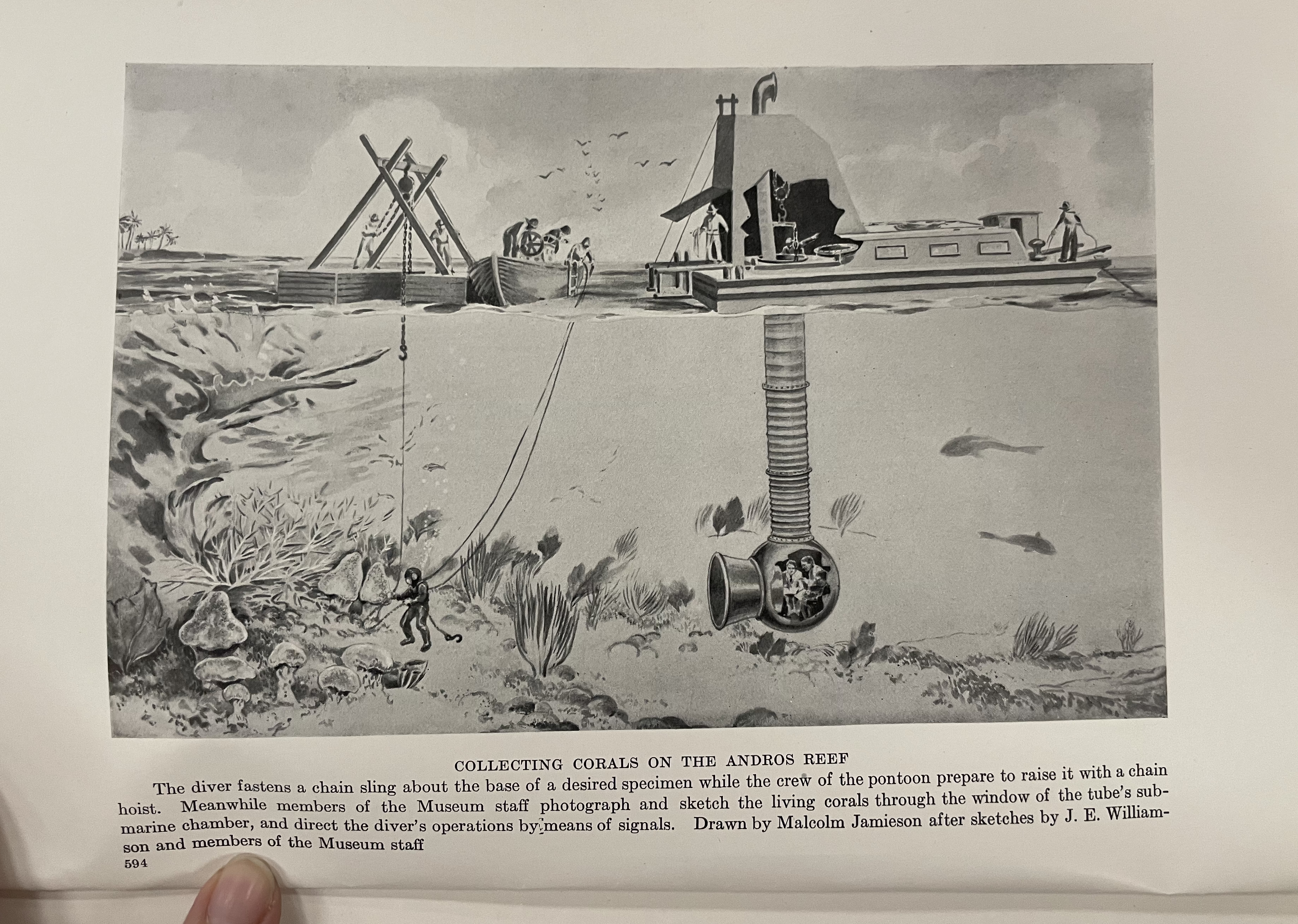

Only a few years prior, Williamson used a device called the Photosphere, a submersible with a viewing window, to create the first underwater photographs and moving pictures in the shallow banks of The Bahamas, facilitating imperial expansion into underwater territories of tropical colonial geographies. Enduring narratives about Williamson cast him as a conservator, groundbreaking filmmaker, and major contributor to the Bahamian tourism industry for his visual technologies, as well as the partnership he struck with the local Development Board to make the Photosphere a tourist attraction as the world’s first undersea post office, offering views of the “sea gardens” in Nassau Harbour. But while Williamson received accolades and compensation for making films depicting the beauty of Bahamian seas, he also actively destroyed the ecosystem he exploited. Using his Photosphere, he worked with the American Museum of Natural History to create an ambitious two-story diorama using 40 tons of coral extracted from the Andros barrier reef. Williamson then mined a further 30 tons of coral and fish for a diorama at The Field Museum.

The Photosphere gave us the ability to see and classify the boundlessness of the sea, and therefore domesticate and destroy it. Indeed, the Photosphere had another name: “The Hole in the Ocean”. Prophetic, and one hundred years later, seawater temperatures are so high that the coral remaining in and around these sites, as well as other coral-rich areas of the world, are dying before our eyes. These expeditions required the collusion of governments, institutions, and individuals to freely exploit the natural resources of a vulnerable colonized nation for decades–and none have reckoned with the tremendous loss in its wake.

Seeing a direct connection between these events to our current coral extinction crisis, Sonia is exploring how these expeditions shaped the popular imagination of undersea life and had a long-term negative impact on the Bahamian coral ecosystem. She has been visiting institutional and private archives to better understand the timeline, goals, and results of the expeditions from primary sources, as well as interviews and visits with individuals and organizations actively working to stop and reverse coral extinction to better understand this crisis.

Keeping in line with her creative practice of working with historical texts and archival materials as her primary sources of inspiration through which to subvert the visitor’s/tourist’s voice/gaze in the region and expose alternative self-actualized narratives, Sonia is exploring how she can re-create these dioramas in a single fragmented ephemeral state. Her outcome is to make visible this historical act of plunder while drawing attention to the gap between what was and what is, especially in this current moment of devastating coral ecosystem loss.

To that end, she recently took the workshop “Pulp, Paint, Play” with Claudia Borfiga at the Women’s Studio Workshop in Rosendale NY to deepen her knowledge of pulp painting in order to utilize the medium to re-create the dioramas.